Today’s Voice of Kidney Cancer is Dr. Elizabeth (Lisa) Henske, who runs the Henske Lab at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. One of her principal areas of research is chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (chRCC). She’s also one of the newest members of the KCCure scientific advisory board. We’re grateful to Dr. Henske for donating her time to answer a few questions about her work in chRCC.

ChRCC is a rare subtype – only about 5 percent of kidney cancer patients have this pathology. For patients, it can feel like no one is really focused at all on this disease. From your perspective, what are the latest advances? Is there new information that we’ve learned in the past few years that is changing the field for chRCC patients?

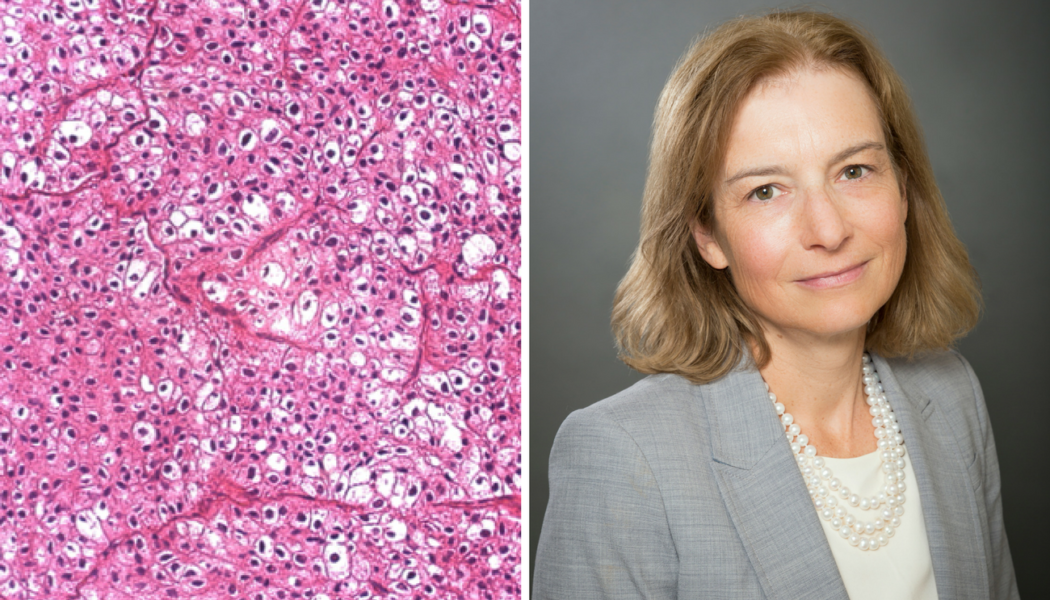

There has been a burst of interest in chromophobe kidney cancers in the past few years. First there was “The Cancer Genome Atlas” or TCGA, which performed the first comprehensive analysis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (chRCC). This important paper, published in 2014, is essentially our first “road map” of chRCC. Surprisingly, these tumors have a very small number of DNA mutations compared with other cancers. So, the road map is incomplete – these tumors must be going “off road” in ways that were not revealed by the initial TCGA study. Some of these off-road trails have been clarified through elegant work by James Hsieh (now at Washington University in St Louis) and his colleagues, and through recent work by our group at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. From the clinical trials perspective, there is now a focus on non-clear cell tumors from leaders including my colleague Toni Choueiri at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

These “off road” trails that lead to chRCC appear to involve metabolic pathways, including changes in how chRCC cells resist oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is caused by so-called “reactive” oxygen molecules that can bind to and damage DNA, proteins, and other molecules. Many different cellular processes can produce reactive oxygen molecules (also called free radicals). Cells must detoxify these reactive oxygen molecules by converting them to water (H20), or risk devastating cellular damage. We believe that chRCC cells have a fundamental defect in their ability to detoxify reactive oxygen molecules, leading to a vicious cycle in which cellular damage (especially to mitochondria, where cellular energy is produced) leads to more reactive oxygen molecules leads to more damage. We are currently investigating how these fundamental features can be used to design specific treatments for chRCC.

What are the biggest gaps when it comes to research and chRCC? How are working to close them?

One of our most important gaps is the very small number of cell lines and animal models of chRCC. This limits our ability to study these tumors and to design new therapies. Usually we don’t know that someone has a chRCC until after the tumor has been removed, so we aren’t able to acquire the tissue for research before it has been preserved. This slows the pace of research!

We are working with the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, where I am an Associate Member, to develop new cell culture models of chRCC. The Cell Line Factory, led by Jesse Boehm at the Broad, is an innovative, one-of-a-kind program entirely focused on generating new cell lines, especially for rare tumors or other cancers for which there are few cell line models. For this, we need access to tissue that has not yet been preserved. We urge those who know before their surgery that they have a chRCC to contact us, so that we can use their tissue for this critical research.

What led you to a career in research? And why the focus in chRCC?

I have always been interested in science and medicine, since I was a child. In high school and college, I was lucky enough to spend my summer working at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda Maryland, where my love of genetics began. I majored in Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry at Yale and then attended medical school at Harvard. While I was a resident at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston I realized that a career as a physician-scientist focused on cancer genetics would be ideal for my interests, and I went on to train in medical oncology at MGH, followed by additional research training in cancer genetics.

I continue to see patients with genitourinary cancers, including kidney cancer and prostate cancer. I also patients with rare kidney cancer-predisposition syndromes, including tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome (BHD). My research laboratory has been studying on TSC and related diseases for my entire career. TSC and BHD patients can develop chRCC, and this is why I began to focus on chRCC. Often, a genetic syndrome that causes a rare tumor can fast-track our understanding of the cause of the tumor. One of the best examples of this is the connection between clear cell RCC and von Hippel Lindau disease.

I am extremely optimistic about the future of chRCC research and clinical care. In only 4 years since the very first “road map” we have made tremendous additional progress. New discoveries are on the horizon. We are at a pivotal moment, with a critical mass of physicians and scientists who are dedicated to improving and extending the lives of patients with recurrent or metastatic chRCC.

Are you a newly diagnosed patient with chRCC and haven’t yet had surgery? Would you like to ensure that your tissue, that would otherwise be discarded, is used for research? Contact us or Dr. Henske directly at Ehenske@bwh.harvard.edu for more information. It’s important that this is done as soon as possible prior to your surgery date to ensure that a local team can be in place to deliver the tissue.